How The Miao People Write Stories On Cloth With Wax And Indigo

From melting beeswax to the final boil, this labor of love is a family obligation passed from mothers to daughters. Location: Danzhai, China

The Debate on Origins

I’m from Malaysia, and growing up, I always thought batik was something you’d only find in Indonesia or Malaysia. So when I first came across Miao batik in Guizhou Province, China, I was genuinely surprised. In Danzhai, Anshun, and Zhijin counties, batik is rather prominent.

The origins and global development of batik (wax-resist dyeing) are subjects of ongoing debate among experts worldwide.Japanese expert Takeo Sano suggests batik originated in India approximately 2,500 years ago. He believes the technique moved West to Egypt via Persia in the 5th century, East to China during the Tang Dynasty (7th century), and then to Japan (7th–8th century) before finally reaching Java around 1000 AD. Meanwhile, American expert Ernst Muehling argues that batik began in Java and spread from there to the rest of the world. American author Vivian Stein posits that the craft likely started in either China or Egypt before spreading globally.

While its exact birthplace is debated, historical evidence confirms that batik-like techniques, known as "Ranxie" (dyeing and printing), were already a flourishing skill for silk textiles during the Spring and Autumn and Warring States periods (approx. 400 BC).

This historical timeline challenges the Japanese theory that batik only reached China in the 7th century. Early records include observations by the philosopher Mozi, who famously commented on the transformative nature of dyeing:

"Dyed in blue, it becomes blue; dyed in yellow, it becomes yellow... because the color changes with what it is dipped in, one must be cautious with the dyeing process."

「染于蒼則蒼;染於黃則黃。所入者變,其色亦變,五入必而已則為五色矣,故染不可不慎也。」

The Chinese Batik

The Miao locals call it wutu (务图) in their language, which means “wax-dyed clothing,” though it’s also been known historically as “waxie” (蜡缬) for its wax-resist technique. That was the more formal, historical name used during ancient times. Over centuries, laran (蜡染) became the standard modern name because it perfectly describes the core two-step mechanic of the craft:

Lǎ (蜡): Refers to wax, specifically the natural beeswax or insect wax used as a resist material to create patterns.

Rǎn (染): Refers to dyeing, describing the process of submerging the waxed fabric into a vat, typically filled with natural indigo.

In 2006, Laran was among the first intangible heritage elements to be officially recorded in China as a National Intangible Cultural Heritage, which has helped spur recent preservation efforts.

Zhang, a recognized inheritor of Miao batik, now hosts programs to teach anyone the art of Laran. Here, she’s looking what her students have made with pride.

Cultural Transmission and Lifestyle

These regions are multi-ethnic, and the Miao communities have maintained self-sufficient ways of life, partly because of their long-term geographical isolation. Tradition dictates that every Miao woman must learn this craft. From a young age, girls are taught to grow indigo and cotton, spin yarn, weave cloth, draw with wax, and sew their own garments. Batik shapes how they dress, celebrate festivals, get married, interact socially, and even honor the dead.

Miao batik is mostly for personal and household use:

Apparel: Women’s clothing, head wraps, and bags

Household items: Bed sheets, quilt covers, and baby carriers

Ceremonial items: Shrouds for funerals

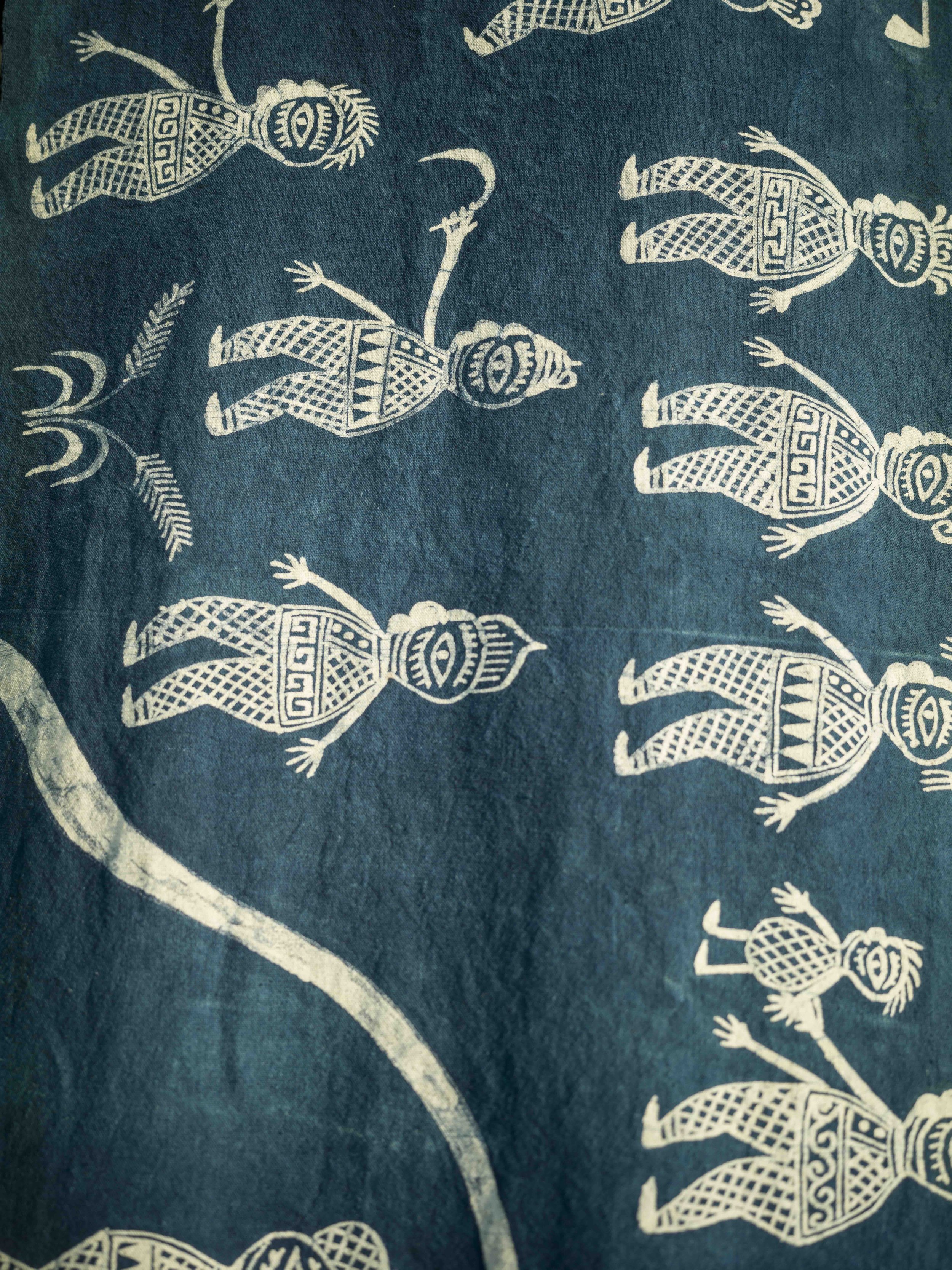

There are two main techniques: wax-dotting and wax-drawing. Patterns are either naturalistic or geometric. Patterns like the butterfly represent the "Butterfly Mother," the legendary ancestor of the Miao people, while fish patterns are auspicious symbols of fertility and prosperity. Legend says a Miao girl once caught a butterfly that taught her the secret of drawing with wax, and a bee later showed her how to use beeswax to make the colors permanent.

Each county has its own signature style:

Danzhai: Bold, lively floral patterns full of rural charm

Anshun: Geometric patterns with a looser, spirited feel

Zhijin: Extremely delicate, dense white geometric spirals, intricately woven

The Miao Batik Pattern: Fish because fish produce many eggs, they are symbols of fertility and prosperity.

The Production Process

The craft follows a precise, interconnected set of steps:

Preparation: Hand-woven cloth is soaked in wood-ash filtered water to remove lipids, so wax sticks and dye penetrates easily.

Wax Drawing: Beeswax or yellow wax is melted and applied to the fabric using a copper knife (铜刀), called a wax pen (蜡笔). It consists of two triangular brass blades tied to a handle, designed specifically to hold just enough melted wax for smooth drawing.

Dyeing: The cloth is moistened and repeatedly submerged in an indigo fermentation vat until a deep blue is achieved.

Dewaxing: The wax is boiled off, skimmed, and saved for reuse.

Finishing: In Danzhai, colors like red (from madder root) or yellow (from gardenia) are painted on afterward to prevent fading.

Like many traditional crafts, Miao batik is under pressure. Technology and the availability of other textiles have shaken its role in daily life. Tourism has created a market for batik souvenirs, but chasing quick profits has led to lots of low-quality imitations, stripping away the symbolism and meaning of the craft. Protecting authentic Miao batik and ensuring it survives sustainably has never felt more urgent.

How to Tell Real Batik from Machine-Printed

When shopping for batik in Guizhou or online, look for these three key "tells" that separate a hand-drawn masterpiece from a machine print:

The "Ice Crack" Test: Look closely at the blue areas of the fabric. Authentic batik has tiny, irregular blue lines called "ice cracks" (冰裂紋) where the indigo seeped into natural fractures in the wax. Machine prints are often too "perfect" and lack these organic, spider-web details.

The "Double-Sided" Rule: Turn the fabric over. Because hand-drawn batik involves soaking the cloth in a deep indigo vat, the color and pattern should be nearly identical on both sides. If the back is significantly lighter or the pattern is blurry, it was likely printed on top of the fabric by a machine.

The Smell of Nature: Give the fabric a sniff! Authentic Miao batik is dyed with natural indigo and often uses real beeswax. It should have a faint, earthy, or herbal scent. If it smells like harsh chemicals or ink, it’s probably a synthetic factory print.

Symmetry and Soul: Hand-drawn patterns using a ladao (wax knife) will have slight variations. If every single flower or butterfly is an exact, carbon copy of the one next to it, a computer likely designed it.

You can check out this travel guide to Danzhai, where I documented my journey in search of Miao batik.

Learn how you can explore the most authentic Miao batik in Guizhou: read travel guide